A novel view of the origins, development and differentiation of Indo-Europeans

Abstract

Indo-Germanists have conceded that the Kentum-Satem division of I-E languages is artificial and obsolete since it (the Latin and Avestian word for 100) is but one of many isogloses. A new division of Indo-European languages as “Core” and “Peripheral” is proposed. Certain developmental stages are identified. This represents a modest paradigm shift.

Introduction

In 1786, Sir William Jones expressed his view that “Sanskrit is of more perfect structure than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, yet bearing to both of them a strong affinity as if sprung from some common source. The same origin have also the Gothick and the Celtick, though blended with a very different idiom, and also Old Persian might be added to the same family.” This was one of the cornerstones of modern linguistics. Additional publications by Friedrich von Schlegel in 1808, Franz Bopp in 1816, and Jakob Grimm in 1819, lead to the foundations of comparative linguistics. Due to exclusive use of Sanskrit,

Persian, Greek, Latin, and Germanic, the name Indo-Germanic was coined [1]. Observe that Slavic was not included.

The Kentum-Satem division of Indo-European languages was finalized by contributions of several authors in 1890. There are continuing discussions about the origin and extent of this phenomenon. Sometimes it was presented as a fundamental division of Indo-European languages. Of the 5 possible explanations of the phenomenon, finely the 3-tectal-seriessystem

prevailed [2], although it is not universally accepted and some authors prefer the 2-tectal-series-system [3]. However, in 1965, G. R. Solta has shown that the Kentum-Satem isogloss was overrated as a diagnostic feature and a tool of true componential analysis. It ought not be revered as a defining wedge, which segregates Indo-European languages into two well-defined entities. It is only a single isogloss among many [2].

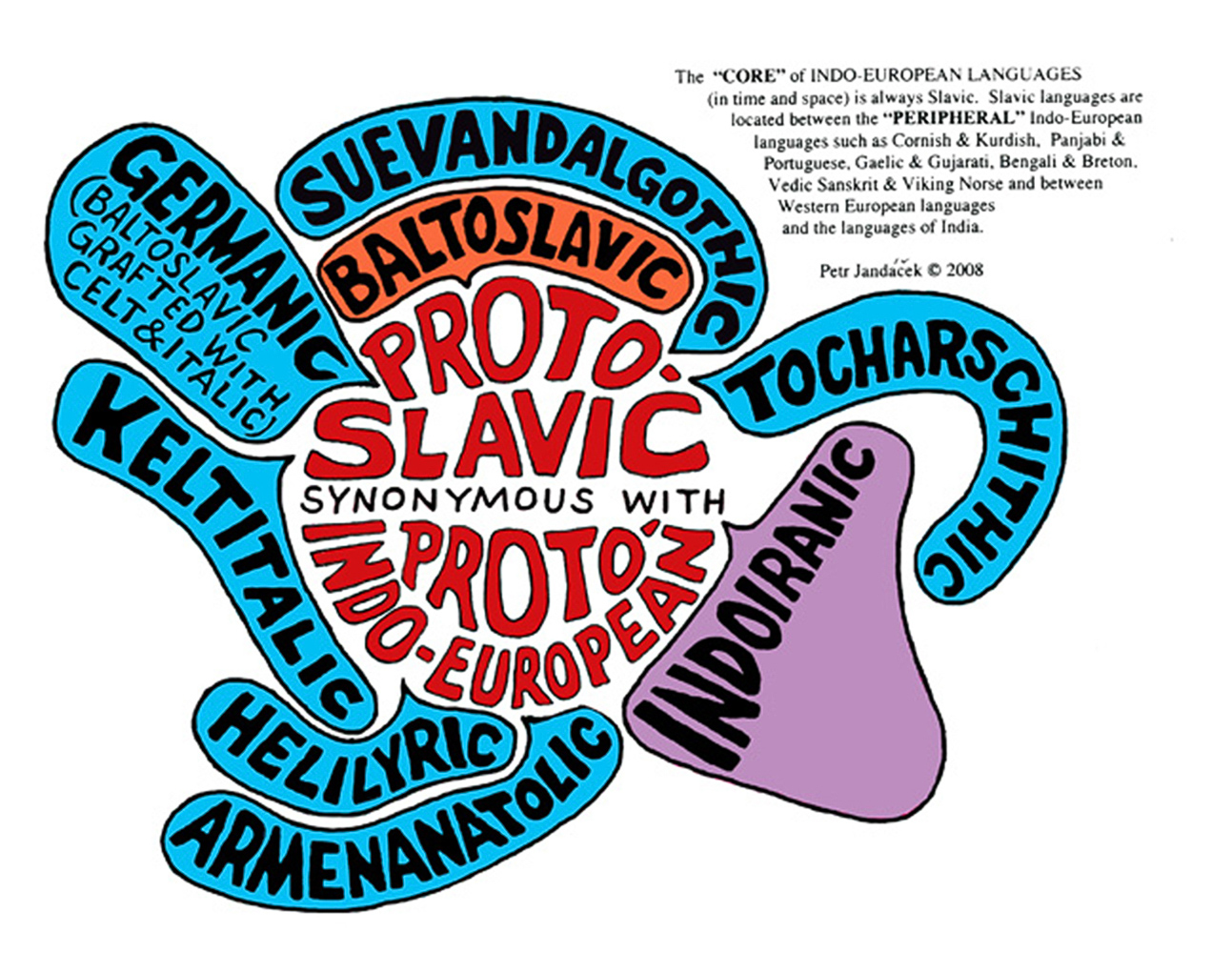

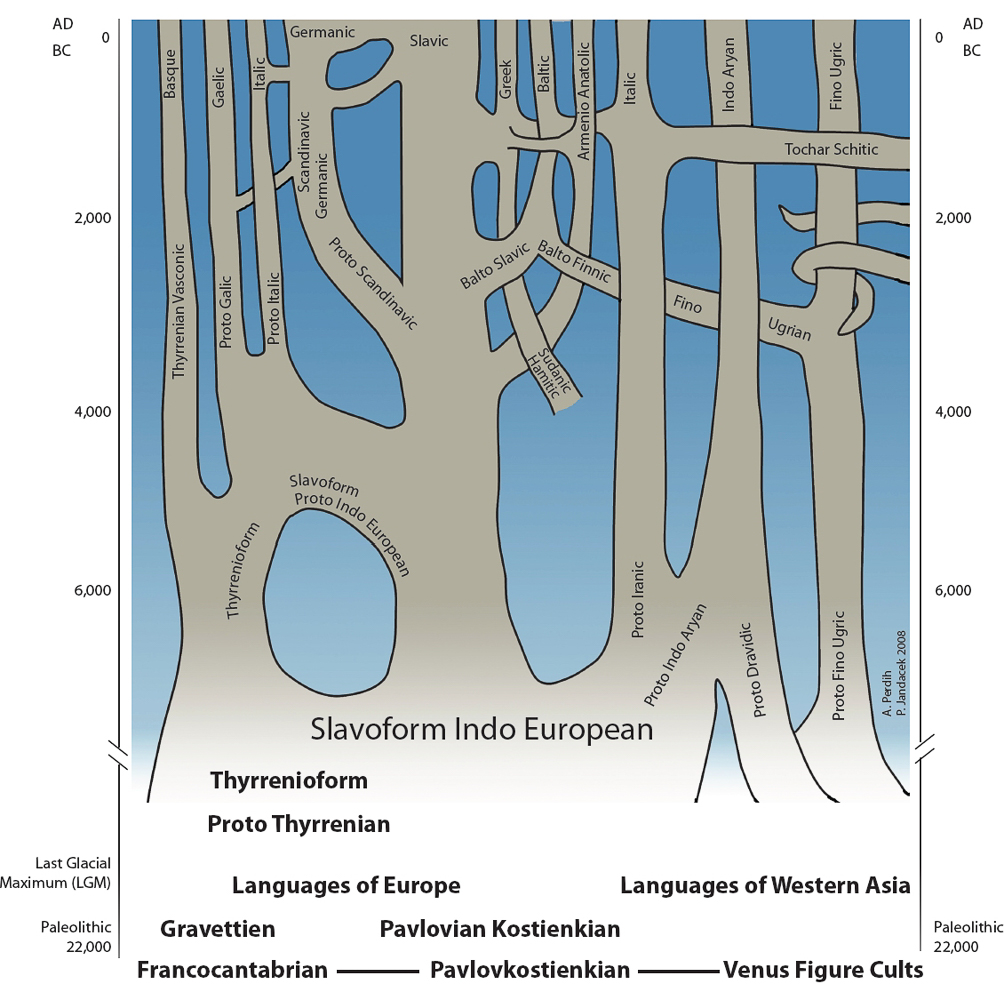

Having observed several Kentum-like events in the so-called Satem languages as well as Satem-like events in the so-called Kentum languages, and being dismayed with the undeserved reverence towards this Kentum-Satem division of Indo-European languages, we approached this question from another point of view. We looked at the Schleicher’s Language Tree, Figure 1, not from the side but from the top. The new view resulted in a different division of Indo-European languages, namely into the core languages and peripheral languages [4]. At the same time, a working hypothesis about the origin of Europeans was presented [5].

The original [4] Core-Peripheral approach needs some revision. However, in any case the core languages remain to be the Slavic ones, whereas the Kentum languages are in any case peripheral. This is well in line with attempts to explain the Kentum effect by the involvement of Sudanic languages, Kafir languages in Hindukush, North Pamir languages, Caucasus languages, Tocharic, and Anatolic languages, cf. [2,3]. Indicative is also the statement of W. Jones expressed in 1786 that “the Gothick and the Celtick are blended with a very different idiom”. The question persists: what would be his opinion if he had used also Slavic. On the other hand, present-day authors contributing to Wikipedia [3] sometimes avoid the term Kentum and refer to Indo-European languages as simply – Satem and Non-Satem. While the Satem languages display integrity and a core of similarities, those languages that used to be called Kentum lack cohesiveness.

There is still the open question whether all languages relevant to clarify the origin of the so-called Kentum languages have been considered. Other Euro-Asian or African languages may yet find an extended membership in (or contribution to) what used to be called “Kentum”. They may include (by some leap of faith) besides those mentioned above also some Ural-Altaic, Finno-Ugrian and even Turko-Tatar and Mongolic. It seems not likely that any more languages would ever join the Satem Core.

It is strange indeed that Non-Satem, which is not integrated – but disintegrated into many dissimilar languages – could have spawned the highly integrated Satem languages. It is more probable that the Slavoform Satem gave rise to the peripheral multiform Non-Satem or Kentum. Uniformity spawns multiformity. Not the other way around. On the other hand, how could it happen that from patently Kentum languages: Latin, Celtic and Germanic, with their various mixing and blending did not produce anything like a true Kentum but rather Semi-Satem if not pure Satem? The linguists explain it by later palatalizations. But, what triggered these palatalizations? At the moment there is no evidence of any other real cause than the Satem substratum. The conquerors of those lands were all Kentum; no one single Satem conqueror of those lands is recorded.

The insecurity of the doctrine of Kentum affirmation is evident in the vacant space depicted by the “gray area” stretching between Eastern Baltic and Northern Adriatic (Diachronic map and the Gray Hole [6] along the Amber Road, Figure 2). This is exactly the area occupied by the ancient Veneti – Venedi (and Wends). The geographic location of the “gray area” also corresponds to the Corded Ware region of the Lusatian culture. Corded Ware horizon and the hypothetical situation around 2000 BC [6] indicate a drastic disagreement between the real situation and the learned construct.

Reasoning

Consequently, the following points are presented:

- German attempt in the 19th Century to marginalize the Slavic role in the “IndoGermanic” Languages was largely successful. This misinformation must be rectified, and the Slavic languages must be recognized as being key to the Indo-European phenomenon. The Slavic languages are not to be viewed as a peripheral branch of the Indo-European Languages, but should be recognized as the trunk of the Language Tree from which the other branches received their substance and sustenance, Figure 3.

- “Indo-Germanic” is a neologism which should be abandoned. Since Indo-Aryans branched off from the “Slavic Mother Tongue” (and “Slavic Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome genes”) some 9,000 years ago [7], and since Germanic Languages branched off from the “Balto-Slavic” source only perhaps 4,000 years ago and subsequently incorporated CeltoItalic elements: “It appears to point to a situation in which Germanic began to develop within the Satem Core (as evidenced by its morphology) but moved away before the final satem innovations. It then moved into close contact with the “western” languages (Celtic and Italic) and borrowed much of its distinctive vocabulary from them…” [8], the term

“Indo-Germanic” is as misleading as there would be in the animal kingdom the expression “Trilobito-Avian” (of trilobites & birds). - We posit that the Slavic Languages as the organic trunk of the Indo-European Language Tree yield better terminology for the language branches. These branches would be Slav-Indoiranic, Slav-Armenanatolic, Slav-Tocharscythic, Slav-Suevandalgothic, SlavKeltitalic and Slav-Helilyric. Thus, for sake of a more accurate understanding of the phenomenon we must create a new lexicon. Based on the 19th Century word choice of “Indo-Germanic” it would seem legitimate to apply a more accurate designation such as “Indo-Slavic”. Similarly, to the west (based on the contributions of Ringe et al. [8]) we are justified in using terminology such as “Germano-Slavic”. Preliminary evidence had suggested to a few linguists that Tocharian A and B are somewhat linked to Italic (KeltItalic). But based on geography, proximity, and the possible migration routes we are forced to accept Slavic as the missing link between western Europe and Chinese Turkistan.

- Dictates of foreign elites (German, Hungarian, Italian, French etc) have been imposed upon speakers of several Slavic languages and/or dialects. However, standardized Slavic “literary” languages have also been forced upon the speakers of dialects. The ancient mosaic of the Slavic substratum throughout Europe was best preserved in those areas where national states failed to impose a standardized language dictated from capital cities. Regional Slavic dialects survived best in Slovenia and adjacent (Slovenian speaking) regions of Italy, Croatia, Austria and Hungary. Similar preservation of dialects survived among the Polabian Slavs, among the Lusatian Wend-Sorbs and in Moravia.

- Remarkably, Slavic elements persisted with great frequency in Old English of a thousand years ago. For example, in the Lords Prayer “Fader Ure” [9] Old English used the Slavic word for “bread” – “hlaf ” as in Chleb, Hleb, Chlieb, Chlib etc. If one reads Psalm 23 in Old English [10] it sounds much like a Slavic language. In this respect Old English is more Slavic than Modern English. Cf. also the case of surnames [11]. Similar observations that an older version of a language is more similar to Slavic than a younger one, have been made also in the case of some other old languages, e.g. Sanskrit (Vedic vs. Classical Sanskrit, as well as vs. modern I-E languages in India) [12], Etruscan [9] p. 344, and Greek (Homer’s vs. Classical) [13,14].

- We can lump certain language branches into “super-branches” like Iranian languages can be lumped with languages of India into Indo-Iranic, and Celtic and Italic languages can form a super-branch “Keltitalic”. But, ultimately all the branches and super-branches issue from the Slavic trunk. The Slavic languages did not grow out of an “Indo-Germanic” trunk.

- Proto-Slavic is in fact synonymous with Proto-Indo-European and aught to be replaced in all literature.

- Slavic languages (because they were the substratum in Europe) continue to be more mutually intelligible than do the more recent Germanic, Romance, Celtic and other languages on the Continent.

- The Veneti of northern Italy and Wendi, Venedi and other Slavic people of western 93 and central Europe and (especially along the Amber Trail) who share similar spelling were the prototype Slavs and prototype Indo-Europeans. From here they had spread to Vladivostok to the east and Greenland (and North America) to the west, and India to

the south east. The Slavic people did not move westward from the Pripyat River marshes merely 1500 years ago but were autochthonic population of Europe since the Stone Age. If there were any Slavic migration of any significance they would be in modern times towards Vladivostok. The Slavic toponymy observed in many parts of Europe [ 15] could

be inherited from prehistoric Venetic-Slav populations or their predecessors.

Consequences

The Core/Peripheral model [4] together with other published explanations [16] seems to be a good tool to explain this.

From the proto-Slavic core in the Southeastern, Southern and Central Europe (originated from the Adriatic, Danubian, Aegean, and Black-Sea refugia during the Last Glacial Maximum) the people expanded, especially after the introduction of agriculture and stockbreeding in Neolithic. On expansion they mixed with the indigeneous settlers of those areas. In the west, proto-Slavic people mixed with those originating from the Thyrrenian refugium turning them Indo-European but not in all instances Slavic. Only the Basques remained there non- Indo-European. They, however, accepted several I-E expressions [17,18].

In the east, the proto-Slavs mixed on the one hand with those living north of Pamir and Himalayan regions, and with these influences they absorbed language features which the 19th Century scholars identified as Kentum (Centum); and to some degree they lost their Satem features. South of Pamir and the Himalayan region became the new homeland of the

immigrants from Europe. Without external pressures for major change they remained in the Satem fold. Satem-like features dominated early Sanskrit, but in post-Rigvedic Sanskrit texts [2] one can detect the appearence of Kentum-like features at the corresponding depreciation of Satem elements under the influence of Dravidian loans.

From north of Pamir and Himalaya, by about 2000 BC these mixed people who had lost several Satem characteristics and obtained a number of Kentum features, started to intrude into Europe as Satem converting to Kentum I-E conquerors, subdueing the peripheral regions of Satem proto-Slavic peoples. The latter lost many Slavic characteristics, but did

not yet change to Kentum. The Greeks, on the other hand, have also Hamitic ancestors [19], who may be intruders into the southern part of Slavdom bringing with them the Kentum characteristics, which some linguists see in Sudan [2].

Timeline

A Time-Line of past events that led to present situation is as follows:

- “Out of Africa” due to warm and dry climate by around 130 000 BP; expansion mainly along the southern European and Asian coasts till about 70 000 BP;

- The Tobe explosion and serious cooling around 70 000 BP; survival of few thousands of peoples, mainly at the coasts, mainly in tropic and subtropic regions; their subsequent slow expansion, also into interior of Europe and Asia; the possibility of some survivals somewhere in East Asia, India, as well as also at the Mediterranean is not to be ignored;

first known symbolic culture [20]; - West Mediterranean survival or expansion from north-west Africa into territories of present Spain, France and Italy of genetic predecessors of present-day Basques, Irish, etc; let us recognise them as proto-Thyrrenians (rather than Italidi [21], since they resided not only on the Italian peninsula but all around the Thyrrenian Sea and in

adjacent lands towards the Atlantic); - East Mediterranean survival or expansion of proto-Slavs from northeastern Africa or from India [22] into the Levant, Fertile Crescent, Aegean, Black Sea and Danube area;

- The 30 000 BP situation where the proto-Thyrrenian people lived from the Atlantic Ocean to the Adriatic and Scandinavia, whereas proto-Slavs populated the areas east of them in the above mentioned areas;

- Till about 20 000 BP retraction into the Last Glaciation refugia; proto-Slavs mainly into the Black Sea refugium, into the Balkans and partly also into the Adriatic refugium; proto-Thyrrenians mainly into the Thyrrenian refugium, whereas more to the south the situation remained largely unchanged. In the refugia mixing and homogenization of people;

- ~ 20 000 BC (Sea of Galilee) first indications [20] of sedentism among people who might have been fishermen; fishermen seem to have been most amenable to develop agriculture;

- By around 14 000 BC there is an expansion from the coastal areas of the refugia northward and into the mountains; especially from the Adriatic refugium as the lowlands near the Adriatic coastline are now below the sea level;

- Hunters were more amenable to develop stockbreeding, stationary or nomadic, possibly after 10 000 BC;

- Fertile Crescent, ~8500 BC: domestication of several cereal species and pulses, as well as sheep, goats and cattle [20]

- Before 6000 BC separation of proto-Indians and proto-Slavs [22,23];

- By about 6000 BC, on the one hand the first expansion of agriculture in the Balkans; by learning, trade, and travel [24]. On the other hand, intrusions of proto-Arabs (or other proto-Semites) into Mesopotamia by about 6000 BC, into Palestine around 1850 BC and massively after the Exodus, by around 1200 BC;

- By about 5600 BC the second wave, more efficient, longer lasting expansion of agriculture, mainly along the rivers, progressively as far as Scandinavia, northern Mediterranean, western Europe and British Isles, causing Indo-Europeanization of substantial parts of indigenous proto-Thyrrenian peoples, and introduction of Slavic-like vocabulary

into Basque. Merging of material cultures [25] indicates Indo-Europeanization of (proto-Finnic [26]) proto-Balts (by proto-Slavs arriving from the Danube area) into Balto-Slavic till about 3000 BC, etc, producing linguistic and genetic clines observable still at present time, and being in line with the Czech and Polish mythology about the arrival there of their ancestors [27]; - In parallel, the expansion of nomadic stockbreeder proto-Slavs from Near East and (South-) Eastern Europe into Central Asia and about 4000 BC reaching as far as China; mixing with indigenous peoples. One of these groups would become later the Tocharians;

- By about 2000 BC, their expulsion by the Chinese; start of their intrusions towards west into Europe; e.g. Hyxos 1750 BC into Egypt, etc;

- Their main intrusion into Europe and Near East after 1300 BC resulting in “Peoples from beyond the Sea” around 1200 BC. Turko-Tataric expressions for leaders of Etruscans [28, 29] as well as the presence of the Y haplogroup HG26 in Italy [23] indicate that they were possibly commanded by Turko-Tatar people;

- After defeats, their retraction into Europe. Subduing the original population and forming “new peoples” like Etruscan, Oscan, Umbrian, Latin; formation of ravaging groups in the central Europe, which promoted defensive architecture (forts) over vast areas;

- By around 700 BC these ravaging groups were driven north into previously protoThyrrenian/protoSlavic Scandinavia, where they mixed and became the foundation stock of proto-Germans, who expanded intruding (approx. 200 BC to 200 AD) south, east and west into traditionally Celtic, Baltic and Slavic regions.

A vignette of this time-line is presented in Figure 4 indicating graphically the course of some events that led to the development of Indo-European languages as we know them today.

Conclusions

Thus, the Kentum I-E languages are derived from Satem ones and not vice versa. These events did not proceed through internal developments in the proto-Slavic I-E languages, but primarily by the influence of proto-Slavic on neighbouring non-I-E languages by events which produce patois, pidgin, creole and other such derivations – as the consequences of elite dominance. And vice versa, by influence of non-I-E languages on parts of protoSlavic. Subsequently, it was followed by elite dominance effect of some of the newly formed Kentum groups over some of the Satem ones.

The massive extinctions of Indo-European languages in the past [30], being it physical or only linguistic, should be sought for not only in Europe, but also in south-west Asia where the development hunter/gatherer > hunter/harvester > mixed farmers (farmers/stockbreeders) might have been performed by proto-Slavs, who in the later periods (e.g. by the sixth millenium in Mesopotamia, after about 1000 BC in Palestine, still later in Anatolia) were subdued, exterminated, assimilated or replaced by other populations or lost their linguistic characteristics due to elite dominance. In Europe, however, the neolithic proto-Slav farmers/stockbreeders seem to have expanded into previously non-Slavic, i.e. non- I-E areas, forming on the one side the Balto-Slavic cline north of Carpathian mountains, whereas north, south, and west of the Alps they effected the Indo-Europeanzation of most of the people descended from the Thyrrenian Sea refugium. After the Roman conquest, and especially after German conquest, the Slavic communities in western Europe (Great Britain, France) and central Europe (Germany, Switzeland, Austria, Hungary, Italy) experienced gradual decline and were finally systematically assimilated during last centuries.

Great caution must be exercised when extracting supposedly *Indo-European features from Baltic languages. Namely, the Balto-Slavic complex had not formed until about 4000 to 3000 BC [25] from the primordial proto-Finnic [26] and incoming proto-Slavic, with later contributions from other sources. It is possible that when a non-Slavic feature found in Baltic

languages is proclaimed as Indo-European, this feature may be in fact non-Indo-European by origin. This warning applies also to other “peripheral” Indo-European languages.

In future research it is imperative also to distill the proto-Thyrrenian features ostensibly preserved in Saami, Old Irish, western Irish dialects (especially in Connaught, Munster, Ulster, Leinster [31]), Old Norse, Basque, Berberic, Sardinian, as well as in the most archaic western and eastern Slovenian dialects.

When doing this type of research, geolinguistic principles are to be considered. However, one must keep in mind, that the rule that “the center is innovative, whereas the periphery is conservative”, is a secondary, not a primary rule. When the languages are in isolation, they are quite stable and change slowly. Whereas, in contact with other languages, they are less stable and as a result change faster. The changes start with borrowings and they increase with the introduction of the logic (structure) of the other language. The combination of both effects is reflected in the innovations. Thus the consequence (and not the cause) is

that “the centers, where different people meet, are innovative. The periphery, especially in isolated places, is conservative”.

And, besides the present [21] static one, a Dynamic Theory of Continuity is to be put together based on the lines presented above.

References

- O J L Szemerényi, Introduction to Indo-European Linguistics, Oxford University Press, Oxford

1996 - J Tischler, Hundert Jahre kentum-satem Theorie, Indogermanische Forschungen, 1990, 95, 63-

98 - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centum-Satem_isogloss, 4. 10. 2007

- P Jandáček, Origin of Speeches, Los Alamos 2000; revised in 2008:

http://www.veneti.info/index.php?view=article&catid=25%3Alinguistics&id=126%3Aorigin-ofthe-speeches&option=com_content&Itemid=165 - A. Perdih, Izvor Evropejcev v luči ugotovitev Tomažiča, Šavlija in Bora (Origin of Europeans

in the light of findings of Tomažič, Šavli and Bor), V nova slovenska obzorja z Veneti v Evropi

2000 – Tretji Venetski zbornik (Into new Slovenian horizons with Veneti in Europe 2000 – the Third

Veneti Proceedings), I. Tomažič, Ed., Editiones Veneti, Wien 2000, 17-27 - D A Bachmann, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Satem, 4. 10. 2007

- J Skulj, J C Sharda, R Narale, S Sonina, ‘Lexical Self –Dating’ Evidence for a Common AgroPastoral

Origin of Sanskrit ‘Gopati’, ‘Gospati’ and Slavic ‘Gospod’, ‘Gospodin’ Meaning Lord/

Master/Gentleman more than 8,000 Years Ago, Vedic Science, 2006, 8(1), 5-24; cf.: Proceedings of

the Fourth International Topical Conference Ancient Inhabitants of Europe, Jutro, Ljubljana 2006,

40-58; http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik06/skulj_sanskrt06.pdf - D Ringe, A Taylor, T Warnow, The Los Alamos Monitor, January 2, 1996, p.1;

http://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/11 - http://rickmk.com/rmk/Pray/ang-our.html

- J Diamond, The third chimpanzee, HarperCollins Publisher, NewYork 1993/2006, p. 275

ISBN-13:978-0-084550-6 (pbk.) - A Rant, Surnames in Swansea Area (Wales, Great Britain) and in Slovenia, Zbornik pete mednarodne

konference Izvor Evropejcev (Proceedings of the fifth international topical conference Origin

of Europeans), Jutro, Ljubljana 2007, 207-212;

http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/ - J Skulj, J C Sharda, Indo-Aryan and Slavic affinities, Zbornik prve mednarodne konference Veneti v

etnogenezi srednjeevropskega prebivalstva (Proceedings of the First International Topical Conference

The Veneti within the Ethnogenesis of the Central-European Population), Jutro, Ljubljana 2002,

112-121; http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik01/htm/skulj_indo.htm - O Belchevsky, A new look at classical mythology with the help of Slavic and Macedonian vocabularies,

Zbornik tretje mednarodne konference Staroselci v Evropi (Proceedings of the Third

International Topical Conference Ancient Settlers of Europe), Jutro, Ljubljana 2005, 135-144; http://

www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik05/belchevsky_myth.htm - O Belchevsky, A study of the origins, connections and meanings of the Indo-European words

reeka, ree, rea (river) in language and mythology, Zbornik tretje mednarodne konference Staroselci

v Evropi (Proceedings of the Third International Topical Conference Ancient Settlers of Europe),

Jutro, Ljubljana 2005, 145-158; http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik05/belchevsky_rea.htm - J Šavli, M Bor, I Tomažič, Veneti – First Builders of European Community Tracing the History and

Language of Early Ancestors of Slovenes. Editiones Veneti, Vienna, Austria; Co-published by A

Škerbinc, Boswell, Canada 1996, ISBN 0-96811236-0-0 - A Perdih, Vplivi zadnje poledenitve na praprebivalstvo Evrope (The influence of the Last Glacial

Maximum on the ancient settlers of Europe), Zbornik posveta Praprebivalstvo na tleh Srednje

Evrope (Proceedings of the conference Ancient Settlers of Central Europe), Jutro, Ljubljana 2003,

41-50; http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik02/perdih02.htm - P Jandaček, L Arko, Linguistic connections between Basques and Slavs (Veneti) in antiquity.

Zbornik prve mednarodne konference Veneti v etnogenezi srednjeevropskega prebivalstva

(Proceedings of the First International Topical Conference The Veneti within the Ethnogenesis

of the Central-European Population), Jutro, Ljubljana 2002, 151-166; http://www.korenine.si/

zborniki/zbornik01/htm/jandacek_linguistic.htm - P Jandaček, Equipment of Ötzi in Basque and Slavic, Zbornik posveta Praprebivalstvo na tleh

Srednje Evrope (Proceedings of the conference Ancient Settlers of Central Europe), Jutro, Ljubljana

2003, 17-20; http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik02/jandacek02.htm - A Arnaiz-Villena, K Dimitroski, A Pacho, J Moscoso, E Gómez-Casado, C Silvera-Redondo,

P Varela, M Blagoevska, V Zdravkovska, J Martın, HLA genes in Macedonians and the subSaharan

origin of the Greeks, Tissue Antigens 2001, 57, 118–127; cf.: http://www.makedonika.

org/processpaid.aspcontentid=ti.2001.pdf - T Watkins, Neolithisation in southwest Asia – the path to modernity, Documenta Praehistorica,

2006, 33, 71-88 - M Alinei, Origini delle lingue d’Europa, Il Mulino, Bologna 1996, 2000

- J Skulj, J C Sharda, S Sonina, R Narale, Indo-Aryan and Slavic linguistic and genetic affinities

predate the origin of cereal farming, Zbornik šeste mednarodne konference Izvor Evropejcev

(Proceedings of the sixth international topical conference Origin of Europeans), Jutro, Ljubljana

2008, 5-39 - J Skulj, Y-Chromosome frequencies and the implications on the theories relating to the origin

and settlement of Finno-Ugric, proto-Hungarian and Slavic populations, Zbornik pete mednarodne

konference Izvor Evropejcev (Proceedings of the fifth international topical conference Origin

of Europeans), Jutro, Ljubljana 2007, 27-42; http://www.korenine.si/zborniki/zbornik07/ - D W Bailey, Balkan Prehistory, Routledge, London, New York 2000

- M Nowak, Transformations in East-Central Europe from 6000 to 3000 BC: local vs. foreign

patterns, Documenta Praehistorica, 2006, 33, 143-158 - V Laitinen, P Lahermo, P Sistonen, M-L Savontaus, Y-Chromosomal Diversity Suggests that

Baltic Males Share Common Finno-Ugric-Speaking Forefathers, Human Heredity, 2002, 53:

68-78 - H Popowska-Taborska, Zgodnja zgodovina Slovanov v luči njihovega jezika, Založba ZRC, Ljubljana

2005 - M Alinei, Etrusco: una forma archaico di unghrese, Il Mulino, Milano-Bologna 2003

- L Vuga, Megalitski jeziki, (Megalithic languages), Jutro, Ljubljana 2004

- J Diamond, P Bellwood, Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions, Science 2003,

300, 597-603 - E W Hill, M A Jobling, D G Bradley, Y-chromosome variation and Irish origins, Nature, 2000,

404, 351

Povzetek

Drugačen pogled na izvor, razvoj in delitev Indo-Evropejcev

Indogermanisti nakazujejo, da je delitev indoevropskih jezikov na kentumske in satemske umetna in zastarela, ker je (latinska in avestijska beseda za 100) to samo ena od mnogih izoglos. Predlagana je nova delitev indoevropskih jezikov na “osrednje” in “obrobne”, ugotovljene so nekatere stopnje kot tudi drugačna paradigma njihovega razvoja.

Authors

Petr Jandacek & Anton Perdih

Figure 1. The Schleicher’s Language Tree

Figure 2. Bachmann’s [6] map of Kentum and Satem languages

Figure 3. Indo-European Language Tree as seen from above

Figure 4. Indo-European Language Tree as seen from the side in the time span from about 8000 to 0 BC.

(505) 672-9562

Petr Jandacek

Louise Jandacek

Mailing Address

127 La Senda Road

Los Alamos, New Mexico

USA

87544